Transcript of presentation by Michael Teys at the 2025 Strata Impact Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 15 August 2025

1. Introduction

1.1. It’s been described as intergenerational theft. Our propensity to ignore or defer our obligations as property owners – the obligation to maintain, repair and replace our collectively owned common property – to leave this problem for the next generation of owners.

1.2. For those of us of a certain age, we can add this to the list of crimes that as boomers we stand accused:

· environmental neglect

· the housing crisis

· economic mismanagement.

The burden of guilt is heavy, but these things are somewhat ethereal. But this latest crime of which we are accused, the crime of neglecting our responsibilities as property owners, has a more immediate, a more personal, cause and effect.

1.3. We might call this new crime, the crime of ‘gross strata negligence’.

Falling between intent to do wrongful harm and ordinary negligence, gross negligence is defined as willful, wanton, and reckless conduct affecting the life or property of another.

1.4. The research I’m presenting today suggests we are fast approaching a spate of gross strata negligence.

1.5. My presentation is in three parts:

· Firstly, an analysis of legislative intervention that has attempted to force owners to discharge their maintenance obligations – the evolution of these provisions demonstrates the band-aid approach from which this presentation takes its title.

· Secondly, a cross jurisdictional comparative study of how these legislative interventions have been taken up around the country – nationally, the band-aids are being used sparingly. Queensland, bless their hearts, don’t know where the band-aids are kept.

· Thirdly, a literature review of papers to see if the legislative interventions are working – are the band-aids helping heal wounds.

I’ll conclude with some thoughts about where we might be heading.

2. The evolution of legislative intervention to enforce the duty to maintain and repair collective property

2.1. The starting point for this study is the fundamental obligation on strata entities to maintain and repair their common property. We find this in the first generation of strata laws from the early 1960’s which has remained a constant everywhere except Queensland which only provides for maintenance, not repair. Elsewhere strata entities must properly maintain and keep the common property in good and serviceable repair. This is a strict liability, reasonableness is irrelevant.

2.2. In Seiwa (2006) His Honour Justice Brereton gave us a helpful summary of judicial pronouncements about the of the duty:

· The duty is compulsory not optional, which is one of the key things that makes strata different to other forms of property ownership.

· The duty is absolute, and not a duty to use reasonable care or to take reasonable steps. If it’s broken it must be fixed immediately – you can sort out later who pays.

· The duty extends to remediation of building defects caused by the developer.

· The duty requires common property to be fixed even if it pertains to only some, but not all lots.

· The duty is owed to each owner, and a breach of the duty entitles an owner to recover from the owners corporation, as damages for breach of statutory duty, any reasonably foreseeable loss suffered by the owner because of that breach.

2.3. The WA case Drexel London put it well - actual or constructive knowledge of the defect, not lack of care, needs to be shown to establish breach - the strata entity is in the position of an insurer: Drexel London (a firm)-v- Gove (Blackman) [2009] WASCA 181.

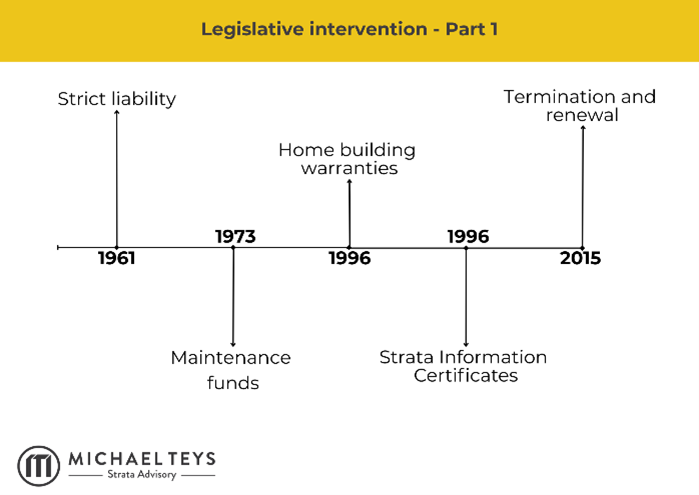

2.4. Since the early 1960’s, across the nation, there have been 10 major categories of legislative intervention to enforce the fundamental obligation to maintain, repair, and replace common property. NSW is the only state to have embraced each of these interventions and is therefore the frame of reference for my research.

2.5. Legislative reform in this area is a two Act tale.

2.6. 1961, strict liability to maintain, repair and replace becomes the first principle of strata. Over the decades this has been extended, for example, to provide a statutory right for lot owners to sue the strata for economic loss.

2.7. By 1973, we became required to keep a separate maintenance fund so funds for major maintenance work and capital reserves are not co-mingled. This legislative category develops over the years to incorporate maintenance plans and studies.

2.8. 1996 is a significant year for strata reform.

2.9. Statutory home building warranties are implied in all contracts for strata, giving owners the right to sue builders for defective work.

2.10. Strata information certificates are required, giving purchasers some insight into the internal affairs of the strata entity – although as we will see the information required to be disclosed is not always the most helpful.

2.11. 2015, we see the ultimate solution to the failure to maintain and repair property first become law – the power to terminate a scheme with a reduced threshold –this makes collective sales, and redevelopment plans an option for those that can attain a super majority of 75 percent.

2.12. What comes next is literally a tectonic shift in this reform agenda.

2.13. On Christmas Eve 2018, Opal Tower failed structurally, and the occupants of 392 apartments were evacuated - fortunately without loss of life or injury. Led by a charismatic chairperson named Shaddy, with a talent for media, the owners corporation mounted a superbly effective campaign to hold the builder and the government accountable for their loss. In this saga, if Shaddy played Robin, then the newly appointed NSW Building Commissioner, David Chandler, was his Batman. And together they took on all comers, and recovered over $31M in damages and rectification work from the builder, and a further $52.8M before legals and litigation funding costs from the developer, builder, their insurers, and others. Despite these successes, most units remain below their 2018 prices.

But perhaps the greatest legacy of Opal Tower, is the raft of very courageous and innovative legislative reform that followed, which goes to the heart of building defects, and consequentially, ongoing maintenance and repair issues. These reforms are a dramatic change from the previous approach. If not Opal Tower’s legacy, this will certainly be Chandler’s.

2.14. These reforms are not without their critics, and are yet to be tested and analysed for their effectiveness, but these reforms are nevertheless brave and mark a new way forward. A way forward that to date has only been adopted in NSW.

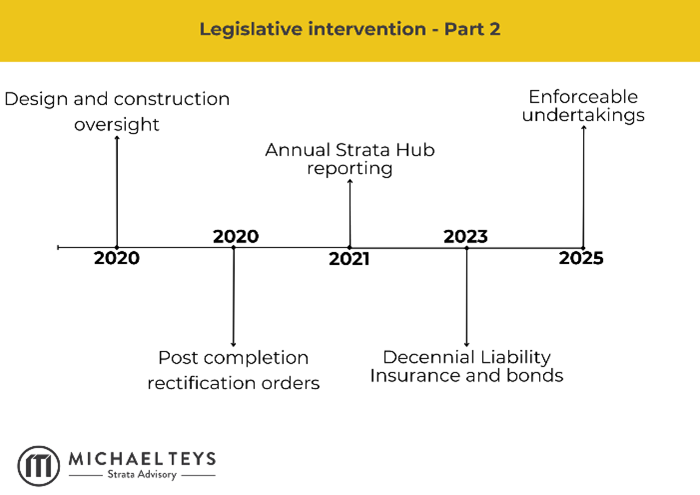

2.15. In 2020,the Design and Building Practitioners Act (NSW) is passed requiring ‘as executed’ plans and specifications to be registered with the government during construction. The Act creates a duty of care for economic loss and personal liability on designers and builders who are no longer protected by the corporate veil.

2.16. The Residential Apartments Buildings Act (NSW) is also passed giving the Building Commissioner powers to investigate and stop work, and issue rectification notices in late stage and newly completed buildings. This has been used to great effect, including at Opal Tower where, for example, an agreement was reached to extend the defects period to 20 years.

2.17. 2021, annual Strata Hub reporting is introduced, requiring owners corporations to file a return with the government each year, which among other things requires disclosure of the buildings insured value, and the balance of the capital works fund.

2.18. In 2023,decennial liability insurance is introduced, providing 10-year coverage of serious defects in critical building elements as an alternative defects bonds(3 percent of the construction contract price).

2.19. In 2025, the Strata Schemes Management Act (NSW) is amended to enable the Strata and Property Services Commissioner to investigate non-performance of strata obligations like, for example, the failure to comply with maintenance obligations by owners corporations, and to accept from the Commissioner enforceable undertakings by which they undertake the repairs and pay for independent supervision of the agreed work.

2.20. This raft of legislative reform marks an important departure from the pre-Opal Tower legislation about repairs and maintenance. Pre-Opal Tower, NSW was on the neoliberal - light touch - self regulation path. In the aftermath of Opal Tower, and of course in the shadow of Grenfell Tower and the death of 72 people including children and entire families, the political will was right for a new approach. An approach that is far more inquisitorial, supervisory, and punitive– the likes of which we haven’t seen since before the private certification of developments in 1998. It is also an approach, as we will see, that is markedly different to the approach being taken elsewhere in the world in response toother catastrophic events in tall buildings.

3. The take up of legislative reforms on maintenance and repairs across the nation

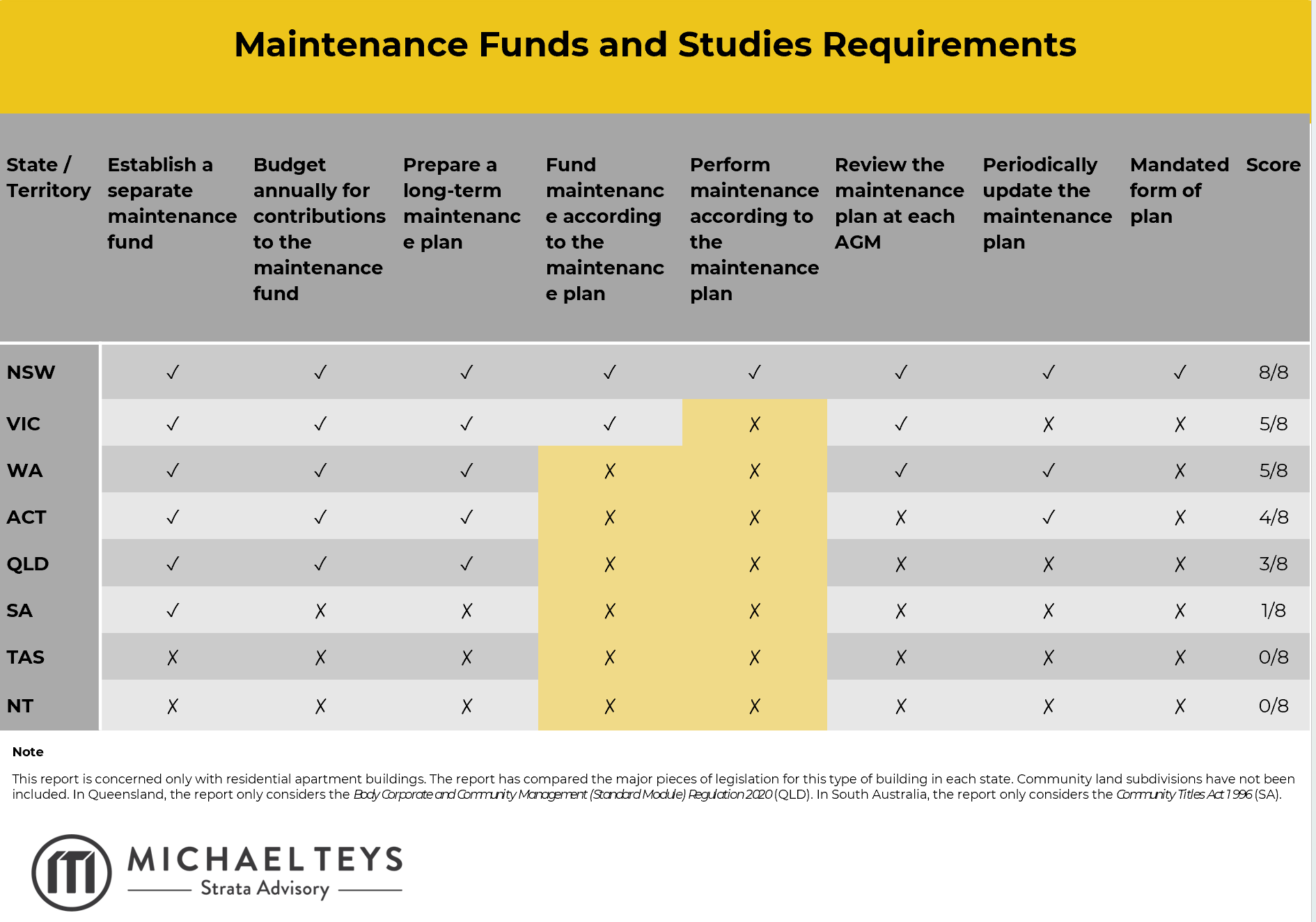

3.1. In the way of Australia, and strata laws in particular, everyone must do things differently. This area of the law is no exception. The cross jurisdictional comparative law study that is with your conference papers proves the point.

3.2. This part of my research takes the 10 categories of maintenance and repair legislative reform I have identified and looks at the way these categories have been expanded and adopted in each state and territory.

3.3. For elementary comparative purposes, I have given each provision of the national suite of these laws one point, although of course, some provisions may be more worthy than others of a higher score.

But, for example, here is the table on maintenance funds.

3.4. Along the horizonal axis, the table traces the expansion of provisions about these funds since they first appeared in the statute books in 1973. You will observe the progression of the laws from the establishment of separate funds to the requirement for 10-year plans.

3.5. Having examined all 10 categories, here are some of the key findings to date from this part of my research:

· Seven out of the eight states and territories have less than 50 percent of maintenance and repair provisions applicable in their jurisdiction. This represents over 2.1 million apartments without the benefit of these laws. NSW is the out performer with a score of 44 out of 47.

· Maintenance, repairs and replacements do not have to be performed according to the maintenance plan in all states and territories, save for NSW. In these places, maintenance plans are a mere suggestion.

· Strata Information Certificates do not include disclosure of outstanding building defects nor disclosure of unfunded repairs and maintenance anywhere in Australia.

· Victoria has not followed NSW with an extensive regime of supervisory and interventionist regulatory powers during the design and construction phase. Victoria has adopted some of the interventionist provisions of NSW including pre completion inspection and surveillance visits during construction. All other states and territories are yet to legislate in this way.

· Post construction rectification work, including rectification orders, stop work orders, and investigative and remedial powers, now exist in NSW and Victoria but not elsewhere.

· Annual strata entity reporting has been introduced in NSW, including information about the balance of the maintenance fund. No data has yet been released. Western Australia has begun tracking the number of schemes managed by each strata manager but not details of the governance of the schemes.

· Victoria and NSW now have defect bond schemes on new construction. However, only NSW has Decennial Liability Insurance. Decennial Liability Insurance will only be given in NSW where the developer and builder have an acceptable independent iCert rating.

· Enforceable undertakings, including extensive investigative powers to require information and answers, issue search warrants, require the assistance of occupants and the strata entity, to seize and test materials, and issue compliance notices, exists only in NSW.

4. Are the band-aids working?

4.1. So, we have looked at the band-aids and where they have been applied, and identified some areas the study shows as deficient, but the broader question arises. Are the band aids working? Perhaps the better question is – do we have a problem? Because the fact is, that like so many things in strata, we don’t really know.

4.2. We don’t know how much money is sitting in maintenance funds, and what this is as a percentage of the replacement value of these buildings.

4.3. Around the world, various countries have moved to prescribed formulaic contributions to maintenance funds. These types of provisions take two forms– a contribution set as a percentage of the replacement value of the building, or as a percentage of the administrative budget. For example, in British Columbia the maintenance fund contribution each year must be at least 10 percent of the administrative fund. This accords with the requirements of the American mortgage insurers, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, that now stipulate that banks can only lend to purchasers buying into buildings where the maintenance fund levies are at least 10 percent of the administrative fund. In South Africa, it’s 25 percent of the admin fund that must be raised annually for the maintenance fund. The Strata Hub data in NSW, not yet released to the public, will be the first insight into this ratio and what we might need to do to catch up with these world benchmarks, if indeed this is a better way to enforce compliance.

4.4. More fundamentally however, we don’t know the full extent of the cost of defects and unfunded maintenance and repair work.

4.5. Above all we don’t know why strata people make bad choices. We don’t know why good people who would no sooner break the law than fly to the moon, are committing gross strata negligence – a willful, wanton, and reckless disregard for their obligations and the safety of others.

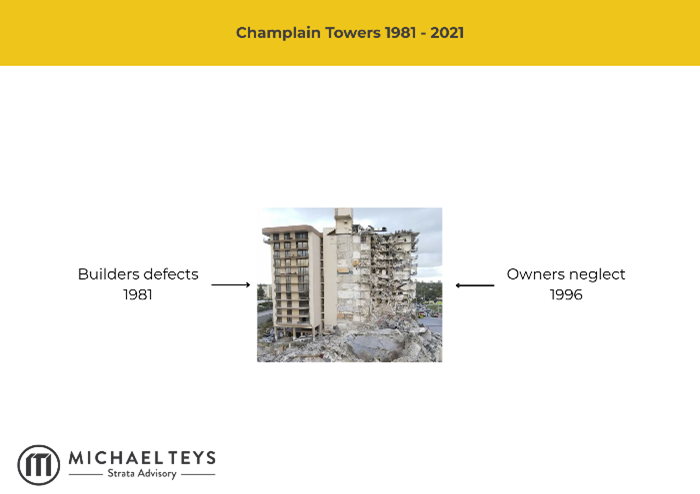

4.6. To explore the socio-legal implications of the things I’m studying and have talked about today there is no more instructive case study than the tragedy that was Champlain Towers.

4.7. On 24 June 2021, Champlain Towers South, a condominium building in Surfside, Florida, collapsed suddenly during the night, killing 98 people. An investigation into the cause of the structural collapse is yet to be completed, however, enough is known about this tragedy now to form some conclusions that illustrate some of the inadequacies of our approach to maintenance and repairs today. This sad case serves our purposes in exploring this area for a number of reasons, not the least of which being that as the post catastrophe studies are coming in, the cause of the collapse was a combination of building defects when it was built in 1981, and neglect by the condo owners at least since 1996 – some 25years before the tragedy - when they received the first of a number of expert reports identifying serious structural issues.

4.8. Let’s look at some of the aftershocks of Champlain Towers.

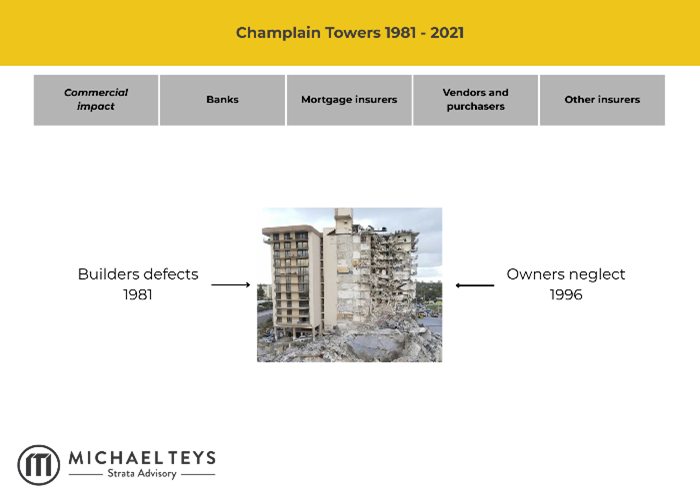

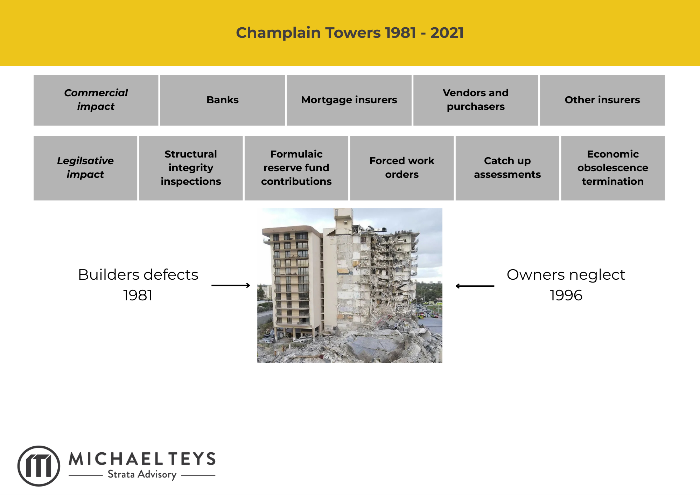

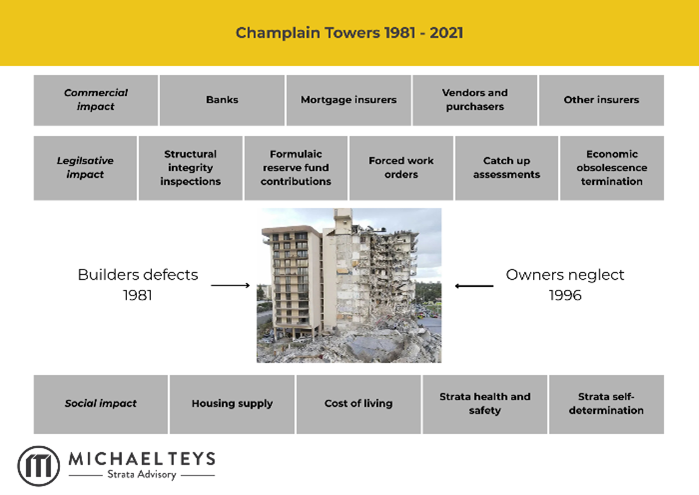

4.9. The markets always react to these signally event first. The US federal mortgage insurers Fanny Mae and Freddie Mac who buy residential apartment mortgages from the banks took only four months to react, issuing policy change that condos with significant deferred maintenance and inadequately resourced maintenance funds would be ineligible for purchase. Plus, they also introduced the minimum annual contribution of 10 percent of admin funds I mentioned earlier. This policy change has made buying and selling some apartments harder.

4.10. The legislatures of America, and in particular Florida, have too responded forcefully with a range of new provisions, all of which are more directed to the enforcement against owners than they are in the way of the supervisory and interventionalist reforms of NSW. The changes in Florida and other US states include -

· mandatory structural integrity inspections at 30 years and then each 10 years thereafter

· catch up assessments to match the cost of the work to be done

· formulaic minimum reserve fund contributions of the type we discussed

· orders against condos forcing work to be done

· and the ultimate solution, termination orders in cases of economic obsolescence.

4.11. Of course, these reforms are only as good as the commitment by various governments to fund education, surveillance and enforcement. Indeed, Champlain Towers is located in the Miami Dade County where there was an obligation for 40-year inspections, but the Department responsible had only one inspector with a 5year backlog of 6,400 pending cases in the city of Miami alone. This included 2,212 buildings for which a 40-year rectification report had not been submitted, 1,606 buildings with reports submitted but not approved, and 2,582 buildings tagged as unsafe.

4.12. The commercial and legislative impacts of Champlain Towers are having a significant social impact, and not just on condo owners. The doyen of world strata academics, Professor Evan McKenzie, University of Illinois Chicago, writes in the recently released Private Law and Building Safety (2025) of ‘the public dimension to this private catastrophe’ where he notes –

· The new laws have effectively raised the cost of living for condo owners.

· The inability of condo owners to fund the catch-up assessments is leading to foreclosures, and even deconversions of condos by developers snapping up disrepair buildings at redevelopment opportunities but with owners taking heavy losses – we have already seen this play out in Sydney at Mascot Towers.

· The legislative paradigm shifts to get tougher on condo owners has been made without institutional support and funding for better outcomes – he suggests some form of government backed low cost loans will ultimately be required but this brings with it obvious political trouble.

4.13. So, why did it happen? And why did it happen when Florida at the time had many of the laws that we have and had before Opal Tower? The preliminary conclusion I’ve reached, is our pre-Opal Tower laws about repair and maintenance, premised as they are on the assumptions that self–interest, preserving property values, and strata being good corporate citizens, are misguided.

4.14. If this is right, and my hypothesis needs more work, then it begs the question –will the second tranche of legislative intervention on maintenance and repair law, the NSW lead post Opal Tower laws, be more effective?

4.15. By turning away from the soft touch self-regulatory laws that have dominated the western world for the past three decades, and adopting an interventionist hardcore heavy hand, will we end up with better, safer buildings.

4.16. For the sake of these 98 people who died in Champlain Towers and their families, and the 4.2 million people that live and work in the buildings we manage, we had better hope so.